Brain in Hand helps Lola’s mental health

Lola is a 43-year-old who identifies as ADHD, has been diagnosed with autism, PTSD, and generalized anxiety disorder. They've been using Brain in Hand for about five years.

Since using Brain in Hand, Lola's confidence has grown significantly. This newfound confidence has led them to become more active in the community. Lola now works full-time, volunteers, plays the cornet in a band, and attends a gay church - all things they started after using Brain in Hand.

“I think I am generally happier to go out and about now. I was almost stuck at home because I was too frightened and anxious to go anywhere. But BiH has helped me plan, chunk it down and break it into steps. I need small chunks, and so following these chunks and being able to tick it off gives me a little dopamine hit. 'I stood at the front door and took a deep breath, and yes I closed it but I did it.' Those little steps and chunking it down to little steps really helped.”

Lola, the chair of a neurodiversity network at work, actively recommends Brain in Hand to colleagues who could benefit from its support.

“It's been massively life changing for me. In my role at work in the network chair, I've got 10 of my colleagues using BiH now because I referred them. I really believe in it; I think it is such a good thing.”

Being able to ask for help has been important for Lola. Previously, ringing services was difficult as there wasn’t a strategy in place to support them in the process. Now, they have increased confidence to use these services through using the strategy section on the app.

“I've got cut and paste text in there to send a text message or an email and I've got all the people I need to text or email and the exact messages I need to send them are all on there. I've worked out with my key worker, and I shared this red-amber-green thing so it's recorded on my healthcare record now as well that if I do ring the crisis team that I've got another cut and paste that I can put straight into a speech app I use when my voice shuts down.”

Lola credits Brain in Hand with significantly improving their mental health. They explained that before using the app, they had experienced hospitalisations for mental health issues. They fear a return to these problems if they stopped using Brain in Hand.

“I think I would have probably been in hospital a number of times again; I've been in and out of hospital for years and years, so I think I would’ve been in and out of hospital still.

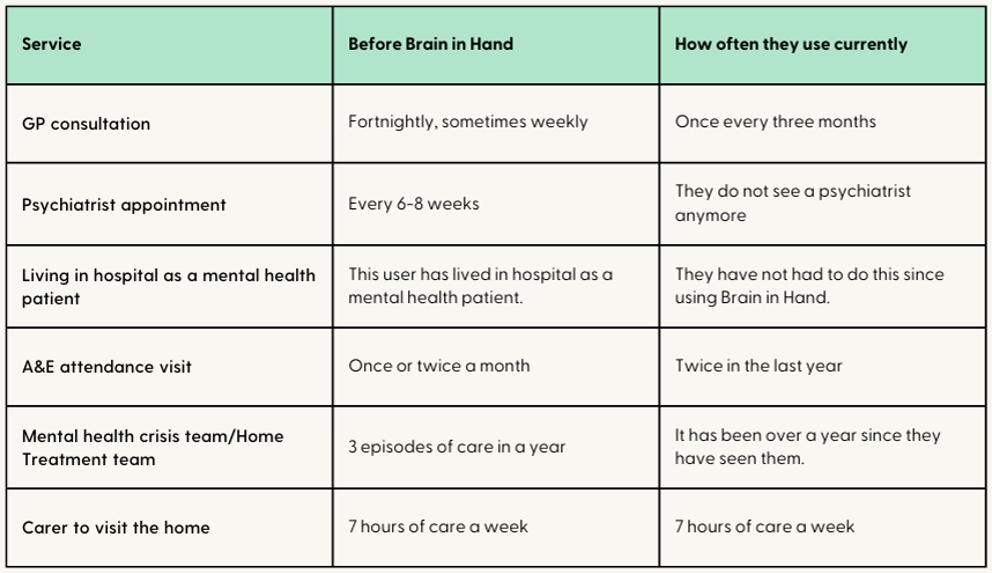

Many of the services Lola accessed in the past have now decreased in frequency using Brain in Hand (see Table 1).

Table 1: Service use before Brain in Hand and since using Brain in Hand

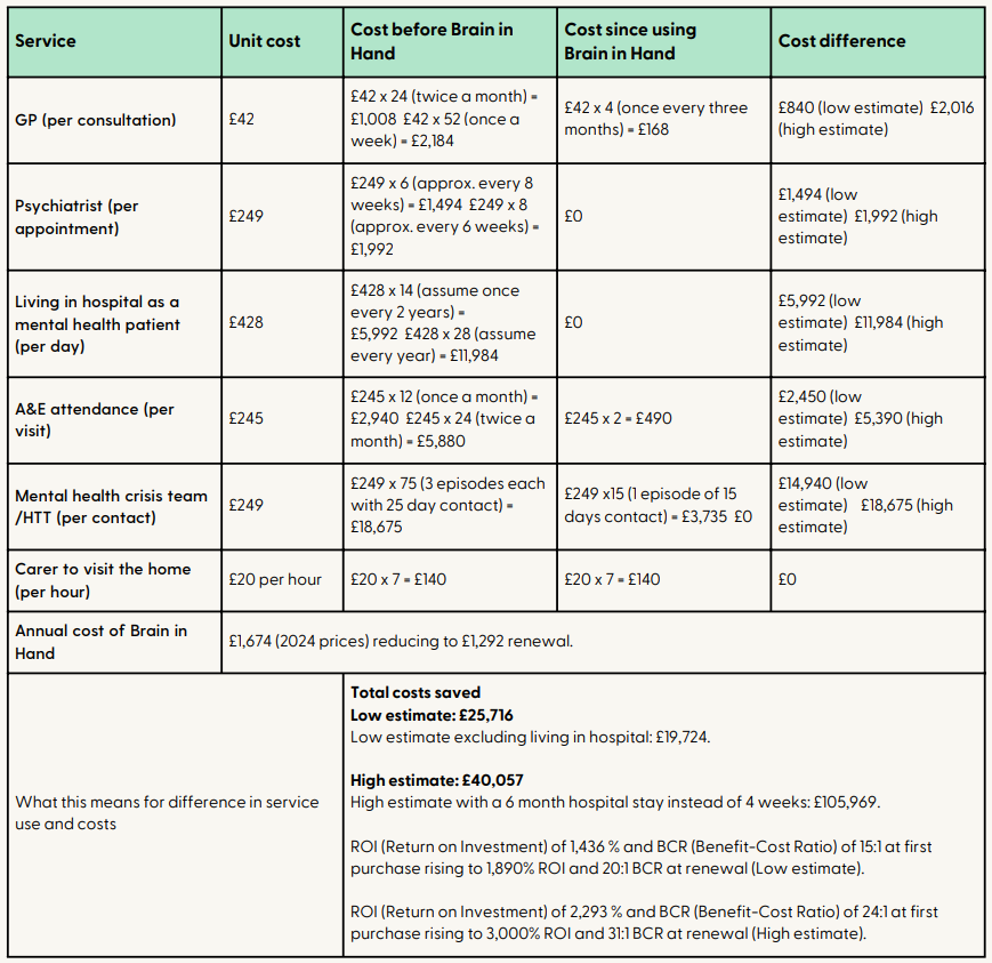

What the findings tell us about averted financial costs

As Table 1 indicates, there has been a decrease in several of the services Lola previously used, specifically GP and A&E visits, psychiatrist appointments, mental health crisis team support and admission into hospital as a mental health patient.

We can calculate that the reduction from attending the GP twice a month to four times in the year (20 fewer visits), generates an estimated annual cost saving of £840, rising to £2,016 for weekly visits prior to BiH (Table 2).

Lola shared they are no longer seeing a psychiatrist regularly (they used to have appointments every 6-8 weeks). However, they shared they do still see a psychologist for blocked therapy treatments. The cost saving for no longer having 6 psychiatrist appointments every year (equivalent to every 8 weeks) amounts to £1,494, rising to £1,992 for preventing 8 appointments (every 6 weeks).

Lola used to go to A&E for their mental health frequently, at once or twice a month. Since using Brain in Hand this has reduced to twice in the past year. This significant decrease in attending A&E shows how Lola’s mental health has improved, and less crisis situations are reaching the point where a visit to A&E occurs.

Similarly, Lola has lived in hospital as a mental health patient but has mitigated this from happening since using Brain in Hand. A reduction in A&E visits from 12 to 2 each year results in a cost saving of £2,450. This rises to £5,390 if the upper range of A&E visits are assumed (24 a year).

In the initial interview, we did not explore the duration of Lola’s stays in the hospital. In a follow-up conversation, we learnt that since the age of twenty, they had at least one admission of 4-6 weeks every few years or more, more often longer, with a few instances of 6 months on a ‘section 3’. This is supported by published evidence that suggests a median stay of 4 weeks (increasing to an average of 7 weeks). (Wyatt, S., Aldridge, S., & Callaghan, D. (2019). Exploring Mental Health Inpatient Capacity.)

Assuming the more conservative estimate of 4 weeks in a year and a cost per day of £428 provides a total cost saving of £11,984 per admission (28 days), noting that avoiding a 6-month stay (around 182 days), which Lola has experienced in the past represents a potential avoidable cost of more than £77,896. Even if their stays in the hospital were assumed to be every 2 years at the lower band of stay (4 weeks), this would result in an annual saving of £5,992.

“I always had a rapid decline into severe psychotic decompensation due to the impact of not sleeping. I didn’t have ways of catching this soon enough or communicating what was happening when I was still able to, before the illness took hold.

Now, I use BiH to copy and paste what I need to express to professionals, even when autism makes it difficult to speak. When the psychosis appears, it’s so hard to order my thoughts and harder again to communicate them orally.

With BiH, my thinking is already there, and what I need to ask for has been input by me when I was well enough to know what would help if/when I need it.”

The mental health crisis team is a service Lola has had support from in the past and they also referred to them as the Home Treatment team (HTT). Before they had access to Brain in Hand, a common pattern would be three episodes of care in a year starting as two weeks of daily contact followed by two weeks of every other day and a further month of weekly appointments.

Each episode therefore represented 25 contacts. They recorded this happening in 2018 and 2019. They found it difficult to recall HTT input during the covid times of 2020 and 2021 but note that in 2022 they had a month of every other day visits for one episode (equivalent to 15 days).

In 2023 they had no contact with HTT except some one-off telephone support calls. Although the interactions have been complex, there has been a definite decline in their utilisation of HTT since using Brain in Hand.

Avoiding the 3 episodes of care in previous years, equivalent to 75 contacts, would represent a cost saving of £18,675. If it was assumed that Lola still accessed the team similar to 2022 (15 contact days), then the saving would be £14,940.

Table 2: Cost breakdown for service use

Based on these costs, at the more conservative estimate of the lowest frequency of visits or reduction prior to Brain in Hand there is a predicted annual cost saving of £25,716, with 19% of these costs being attributed to reductions in GP, A&E and psychiatrist, 23% to savings from living in hospital as a mental health patient and 58% to reductions in contacts with the mental health crisis team.

If the upper range of avoidable service access is used, the annual cost savings rise to £40,057.

Based on the current purchase price of the full package Brain in Hand of £1,674 (£1,395+VAT) for the first year, this provides a ROI of at least 1,436% and potentially as much as 2,293%.

Given renewal rates of £1,292 per subsequent years the minimum ROI would rise to 1,890%. An ROI of 100% means that for every pound spent, we get that pound back plus a pound. In this example, we have 14 x that at a minimum and potentially as much as 30x.

What the findings tell us about averted economic costs

Since using Brain in Hand, Lola's life has changed in ways that could also indicate economic savings. Their mental health has improved significantly, leading to increased social activity. Lola now plays in a band, volunteers, and attends church – all signs of greater confidence. Additionally, Lola's ability to maintain full-time employment without frequent absences benefits both Lola and the employer.

While our initial interview didn't delve into Lola's work life, a follow-up could reveal even more cost-saving factors. We could track changes in sick leave and volunteer hours, both of which hold economic value. Lola's sick days show a steady decline since starting Brain in Hand in 2019 (except for a physical health absence in 2021). For example, sick leave decreased from 10 weeks in 2018 to just 2 weeks in 2022. Even with some external challenges in 2023, Lola managed their mental health better with Brain in Hand, taking only 4 weeks of absence.

“2023 saw my marriage break down and some challenges with my physical health which impacted my ability to want to care for myself. But even so, I had less than 4 weeks off sick (and all in one block) and only the two A&E attendances for my mental health, whilst also maintaining reduced contact with the GP.

If this had happened before getting BiH, I’m certain there would have been an admission to a Mental Health ward followed by intensive Home Treatment Team work and Psychiatry input again.”

Time off work due to sickness can be valued in different ways. The direct costs due to a loss in salary is usually estimated simply as a proportion of annual salary, including all overheads, but there are additional indirect costs if the time off work reduces the productivity of others in the team or a replacement is needed to fill the gap.

Using a conservative estimate of Gross Value Added (GVA) and 230 working days per year, the average cost per sick day is a minimum of £214, meaning that even a modest reduction in sick days of 2 weeks could represent an opportunity cost of £2,140.

Lola's volunteer work has also steadily increased since they began using Brain in Hand. Starting in 2019 with 1.5 hours a week supporting 4 young people, their commitment grew to 4.5 hours per week with about 20 young people by 2021.

Currently, they volunteer locally for around 6 hours per week with approximately 55 young people aged 4-14, and dedicates an additional 2-4 hours per week to a program with wider geographical coverage. This total of up to 520 hours a year represents a significant opportunity cost. If their time were valued at the UK minimum wage of £10 per hour, Lola's volunteer work would be worth approximately £5,200 annually.

Additionally, Lola's reliance on Mindline calls has decreased significantly. They went from near-daily calls to only 2-3 times per year, often using the service for extra support after utilising Brain in Hand's support features. If we assume an average call length of 20-30 minutes and value the volunteer's time at the equivalent of a private therapist's rate (£50), even a conservative estimate of 150 fewer calls per year could represent an opportunity cost savings of about £2,550.

Considering these additional social and opportunity costs (reduced sickness days, volunteering time and reduced calls to Mindline) the positive economic benefit of Lola using Brain in Hand could total upwards of £14,000 a year.

When combined with the reduction in services through improved mental health in Table 2, this would suggest that at a minimum savings start at £40,000 a year.